In 2003, Philip Morris, parent company of Philip Morris Tobacco and Kraft foods, rebranded itself. The goal of the rebrand was to, in name only, distance Philip Morris’s tobacco holdings from their other, less negatively perceived company properties (like Oreo Cookies and Miller Beer). Thus a new, nonsensical name for the parent company was announced: Altria.

Altria is a meaningless name, designed only to unify a disparate collection of entities and shield less desirable parts behind a nebulous whole.

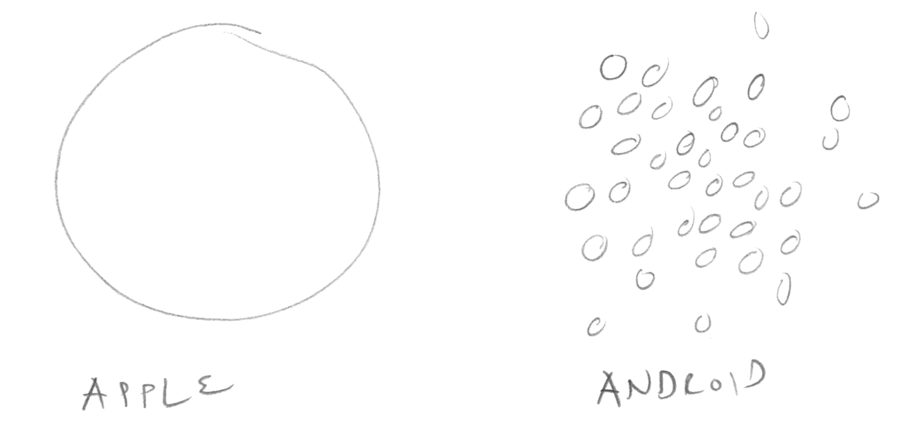

Like the name of the company, Altria’s logo signifies nothing.

Like the name of the company, Altria’s logo signifies nothing.

Five years later, Google’s Android mobile platform launched. Since 2013, Android has ranked as the best-selling operating system on phones and tablets. And since 2013, the name Android has served a role similar to that of Altria: a loose collection of disparate experiences unified under an empty moniker.

Embracing Android’s Potential

In 2015, I switched from iOS to Android. My rationale for doing so was rooted in the realization that, though my phone came from Apple, the software I relied on most either came from Google or was operating-system agnostic (Evernote, Wunderlist, and Spotify, to name a few).

That realization, coupled with the promise of Google’s Material Design, swayed me to make the leap. With Material Design, Google’s software shared a single visual language, and a beautiful one at that. When I envisioned the user experience of Material Design on Motorola’s Moto X phone—a strikingly gorgeous combination of bamboo and dark aluminum—I was sold.

Unmet Expectations

That leap to Android and Motorola, however, landed me on unsteady ground, and my excitement was short-lived. My new flagship phone shipped with an outdated and decidedly not Material version of the Android operating system. To install the new version, Android Lollipop, I had to wait. Until when? Until Motorola released it for use on this specific phone model. Estimated ship date: eventually.

That first impression of the Android universe was underwhelming. I had seen Google’s vision for the future of Android, and this wasn’t it. This just sucked. Things continued to suck for nearly a month.

When Motorola finally released Android Lollipop for my phone, I was (belatedly) impressed. The interfaces and interactions felt intuitive. The animations were snappy. The notifications seemed useful. As more app developers embraced Google’s design standards, the ecosystem of beautiful apps began to rival that of iOS.

Android at its best: podcast controls, weather, file upload, movie download. Simultaneous actions and a clear UI. 🏆 pic.twitter.com/lpHPG10P1p

— Dan Kim (@dankim) May 31, 2016

And then Google announced the next version of their OS, Marshmallow, just a few months after I received Lollipop. Marshmallow’s new features looked truly useful, and I would never get to experience them—Motorola announced that my phone would not receive an update to the new OS.

There isn’t a typical Android experience

Over time, the performance of my phone diminished. The operating system lagged far behind my button pushes and swipes. Running certain apps decreased my battery life percentage in real time. And to remind me of the experience I wasn’t getting, the apps I used were updated to embrace OS features unavailable to me on my still-new phone.

This isn’t a problem unique to Motorola, but it’s a problem nonetheless. And it lands squarely at the feet of Google. There isn’t an Android experience; only an empty brand name shielding a fractured and embarrassing collection of unique occurrences. Altria beget Android. And Android is worse.

Impossible promises

The difference between Altria and Android is that Philip Morris was honest about their intent to hide their less palatable brands from public view. Google promised a better experience through both their design system and their evolutionary operating system. But they also knew full well that they could never deliver on those promises.

Android runs on countless devices from myriad manufacturers across many carriers. With so much variability in device configurations, Google allows each manufacturer to customize Android as needed. This helps Android achieve scale, but also explains how there can never be a universal Android experience.

Google pays lip service to this conundrum by issuing weak threats to some of their manufacturing partners. But these are their partners they threaten—without these partners, Android doesn’t exist at all. Only Apple, by controlling both their hardware and software, can execute the definitive vision they proffer. Android only offers lesser and diminished versions of its promise.

Only Apple provides a cohesive user experience.

Only Apple provides a cohesive user experience.

Attaining a universal experience

Brands often make promises of varying degrees of emptiness, and Google proved no exception. But continuing to issue empty promises erodes trust, confidence, and—ultimately—the user experience.

After reaching my breaking point on my year-old Moto X running a deprecated Android OS, I charged up my 2012 iPhone 5 and started using it full-time. It runs the latest version of iOS. It receives regular updates. And short of some hardware features like TouchID and 3D Touch, it achieves the rich experience Apple promises to everyone.

Android is something different to everyone, but universal to no one. Android is Altria: a loose federation of disjointed parts.