In my role as a researcher on a product team, I spend a lot of time talking to users. It’s always a worthy endeavor—I get to learn about workflows, habits, and the larger context surrounding the person I’m speaking with.

Fieldwork, however, takes those talks and enhances them. Fieldwork offers proximity, and proximity unlocks everything.

A funny thing happens the longer you spend in close proximity with someone—your connection strengthens. You develop a rapport and a sense of trust. Only once this sense of trust is established does honesty emerge.

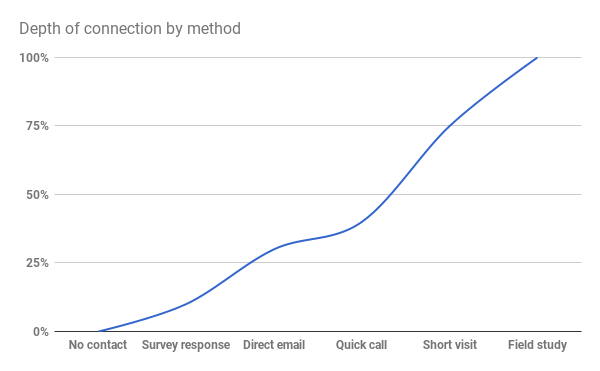

To illustrate, here’s a very unscientific chart that you will not see in the New England Journal of Product Research:

When I managed Mailchimp’s research practice, we performed field studies often. A few years ago, a fellow researcher and I were in Denver, Colorado to visit customers at their respective workplaces. We spent roughly half a day with each customer, learning about their companies and roles and where our product fit in. These hours were uniformly educational—we left each visit with new insights to share with colleagues back at HQ.

Two visits from this trip stand out. On our first morning in Denver, our very first visit was with an ecommerce startup. After a bit of small talk and an hour of conversation about his business, our customer suddenly said that he wasn’t sure he would remain a customer much longer. He was looking at competitors and planning to leave.

He had just presented his ecommerce and marketing operations to us, and described where our product fit in. But he went on to explain that our competitors offered a host of features that we couldn’t match. While disappointing to hear, it was helpful information to understand the process our customer went through to even arrive at this point.

The next day, we visited another customer—a high profile and, by all appearances, model customer. Again, after over an hour of small and shop talk, this customer too announced that he had been thinking of leaving. And he explained his ambitious marketing plans and the tools offered by our competitors and the ways in which we (seemingly) didn’t stack up.

We chose to visit the specific customers on this trip because they seemed to be doing everything right, and using our product to great success. But had we not visited their offices, over a thousand miles away from Mailchimp HQ, we would never have known why they left. We would never have gotten their perspective on why we were no longer the right fit going forward. Instead of being in the dark, we had explanations.

All of this came about because of proximity—because we set aside time to enter the field, gave our undivided attention to our customers, and provided our conversations room to breathe and meander and hold meaning. The proximity of field work pays off.

For more on fieldwork, see my recent Medium post for Jan Chipchase’s Field Study Handbook.